Bellevue School District, school closures, and the data

A look at metrics and the district's budget

Last Friday, January 13, Bellevue School District shared unsettling news: they planned to close three of the district’s eighteen elementary schools. The district says enrollment had declined, they forecast that it will decline for the next decade, and so closing schools is the responsible course to be mindful of tax dollars.

I’ve spent some time over the past week investigating these claims, as well as looking at the district’s budget. I know there’s a lot to digest here. One sentence I hope I’m able to convince you to agree with: we should not close any schools.

Please ask questions in the comments, I’ll be happy to answer. Sorry also if not all of this flows together quite right, I’ve spent my whole Sunday on this and wanted to get it out in front of parents before the Open House meetings that start Monday afternoon.

Executive Summary

I summarize the district’s forecast, including their reasons provided for why enrollment will continue to decline: falling birth rates, high home prices, and pandemic related job movements.

I find that data from the U.S. Census contradicts the claim that we have a shrinking child population. We may have fewer workers in Bellevue, but the data aren’t high resolution enough to tell for sure.

I look at data for private school enrollment and home schooling, and estimate that growth in those two explains at least half of the decline in enrollment. While BSD lost 2,117 students since the start of the pandemic, I estimate that private schools grew by 990, and home schooling added 63.

I look at statewide data and explore data that correlates with growth and decline in school enrollment. High home prices are somewhat correlated, though only at median prices greater than $500,000. Density correlates most closely, with denser areas experiencing declines and less dense areas seeing growth.

I dive into the district’s budget to see how how much of a deficit they’re running and how much they’re spending on other things. Since the start of the pandemic, and despite the enrollment drop, the budget has grown at many multiples of the current deficit.

The District’s Forecast

Melissa deVita, Deputy Superintendent of Finance presented the forecast and the plan to close schools to the school board on Jan 12. That presentation is here.

She frames the enrollment decline as part of a national trend, citing a Wall Street Journal article that says enrollment has declined in 85 of the nation’s 100 largest districts.

She shows that enrollment has fallen from 19,961 students for the 2019-20 school year to 18,808 in the 2021-2022 year. She presents a graph that projects out to 2031, where it is estimated enrollment will have declined to 15,946 students.

She says this decline is driven by three factors:

Declining birth rates

Increased housing costs

Pandemic shift in work environment

She then goes on to describe the district’s plan to close schools and presents the candidate schools. Closing schools is presented as already decided upon, and the only work left is to figure out which schools to close.

Notes on the district’s methodology

The district relied on an outside firm to create the forecast it’s relying on. They released a video showing the presentation that the firm’s owner, Shannon Bingham, presented to the board.

This presentation contains some of the same figures as in deVita’s above, though she appears to have changed and omitted some of the reasons Bingham gives for the decline:

Bingham describes “pandemic losses” as a factor, not limiting the pandemic to merely influencing how people work

Bingham calls out private schools competing for students

I also noticed a quick cut following Bingham’s mention of the pandemic.

Bingham offers some data on housing, stating that we’ll have 35,000 new housing units built during the next 20 years, but that they’re seeing fewer children than expected. While they had expected 1 child per every 40 units, they’re now seeing about 1 child per every 100 units.

He also shows that births in King County are on the decline, that adjacent districts have experienced a decline in enrollment, and talks about trends in housing prices.

I reached out to Shannon via email, asking about the model, its inputs, and whether the model produced ranges of projections or just point estimates.

He replied quickly, in less than fifteen minutes, and gave me a few details:

The model was a “linear cohort survival model calculated on several prior year bases.”

The model doesn’t yield ranges for its estimates.

He said that he’s driving across country at the moment and would get back to me later with more details. He struck me as honest, friendly, and helpful. I was excited to hear more, and sent some follow up questions as well.

Unfortunately, it’s been five days, and I haven’t heard back yet. I noticed that on his reply to me Shannon had copied Melissa deVita. I haven’t heard anything from her, either.

I found a document from OSPI that describes a “K Linear Cohort Survival Method.” The document states:

There are two parts to OSPI’s K Linear Cohort Survival method. The first part, and more universally used, is the cohort survival method. The second part is the K linear approach. Each part is discussed below. The cohort survival method, used to forecast school enrollments, is quite straightforward. One starts with current enrollments, by grade, and then advances students one grade for each year of the forecast. Thus, the current year’s kindergarteners become next year’s first graders. The current year’s first graders become next year’s second graders, and so on. This process can be repeated as many years into the future as desired.

…

The cohort survival method needs some way to obtain future kindergarten enrollments. Currently, OSPI assumes that the recent trend in kindergarten enrollments will continue. For example, if kindergarten enrollment had declined by 5% annually during the last five years, kindergarten enrollment is assumed to continue to decline by 5%. Mathematically, the K linear method requires plotting six years of actual kindergarten enrollments over time and identifying a best fit line using an ordinary least squares regression method. Each subsequent year of kindergarten projections is the subsequent point on the line.

The document goes on to speak to some advantages and disadvantages of this method:

A significant advantage of this method, particularly with respect to SCAGP, is that it is relatively simple to calculate. The only data input required is actual enrollments by grade over time. This simplicity allows the method to be used by the State and districts easily, and allows for transparency in explaining how certain enrollment projections were decided upon.

…

There are two major disadvantages with the K Linear Cohort Survival method, and a third disadvantage inherent in all projection methods.

The first problem is that the method for calculating future kindergarten enrollments is likely to be problematic when the trend in kindergarten enrollments is changing. Exhibit 8 illustrates the difficulties when faced with a change in trend. Five-year historical averages of kindergarten enrollments may not capture cyclical growth rate patterns, therefore over- or underestimating future enrollment, depending on when in the cycle the historical averages were taken.

…

The second major problem with the K Linear Cohort Survival method is that it will poorly forecast enrollments if migration patterns are changing. The most likely situation for this to occur is when there is a substantial change in housing development. For example, if a district expects substantial housing development, and has not recently seen any development, enrollments will be underestimated

And here’s Exhibit 8:

Population-level Trends

U.S. Census

My first stop for checking out the claim that we have a shrinking child population was the U.S. Census. The official census happens once every ten years, but the U.S. Census Bureau maintains an ongoing yearly project to assess population trends called the American Community Survey. The Census Bureau describes it thusly:

The American Community Survey (ACS) helps local officials, community leaders, and businesses understand the changes taking place in their communities. It is the premier source for detailed population and housing information about our nation.

For Bellevue the ACS has 1-year and 5-year estimates available going back to 2010. The difference between these two estimates is described here, but it basically boils down to confidence vs. recency. The estimates are crafted using either one year or five years of survey data. More data means less chance that you’ll by chance get an unrepresentative sample, but having older data in the sample can obscure recent trends.

Given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic, I chose to use the 1-year estimates and look at our school-age populations. There is no 1-year estimate for 2020. Here’s what that looks like:

You can see that, even though the estimate sometimes goes down, the overall trend is up. This is likely an artifact of the smaller segments having less confidence, for the 5-14 group the estimates are expressed with a margin of error around ±1,800.

The Census also does not predict a national trend of shrinking child populations. See this report that projects a growing population of children through 2030, and onward through 2060:

Births in King County

We do indeed have fewer births in King County. We peaked at 2016 with 26,011, and have declined to 23,638 in 2020, the latest year available on the state’s dashboard. I made a chart:

You might think this doesn’t jibe with the Census estimates, but births are only one source of new children in King County. We also have immigration. Unfortunately I can’t find a source that tracks how many kids are relocating to King County every year.

Pandemic-related Job Movements

What about the district’s assertion that the pandemic has resulted in jobs moving away? Is that true? Well, maybe. Unfortunately the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t let me zoom into Bellevue itself, but I can look at King County:

We lost about 10,500 jobs from 2018 to 2021, but that’s out of 1.2 million jobs, a contraction of 0.9%. If those were super concentrated within Bellevue they might have a decent impact, but I don’t know of any source that will tell me if they were.

Private School Enrollment Trends

Hypothesis: the decline in public school enrollment is driven primarily by private school enrollment.

I thought this would be relatively easy to test. We know how much public school enrollment has declined since 2019. Just figure out private school growth since then as well, right?

Unfortunately, the available data on private school enrollment is not so useful.

The state maintains yearly enrollment data for private schools, which I thought would be all that I needed. Nope! There are a lot of problems with this data:

The format of the data is inconsistent from year to year, so each year needs its own set of formulas, pivot tables, etc. It’s also inconsistent within years. For example, some schools have their county listed as “King” and some as “King county.” That’s easy enough to work around, but still mildly annoying.

The 2021 data has many rows effectively hidden, but not using Excel’s row hiding feature. Instead, they’re resized to the point of near invisibility. This threw off my earlier estimates.

There’s no consistent identifier for each school. School names can change, they can be misspelt, schools can divide into two entities or combine into one. Straightening this out took me a few hours. But it turns out that was unnecessary because:

A lot of schools show zero enrollment for 2019. 12 of the 37 schools within the borders of Bellevue School District had big fat zeros. I checked each one to make sure that it wasn’t just established that year, and none were. Some of these schools were decades old and in reality had hundreds of students.

In the 2019 data many of the total enrollment figures don’t match the sum enrollment of all the grades. They can be dozens of students off in either direction.

The federal government maintains a much better dataset, the Private School Universe Survey. It has none of these problems. However, it has no data more recent than the 2019-2020 school year.

At first I thought I could just fill in the missing state data with data from the feds, but as I started doing that I realized that the 2019 figures I did have from the state were often very different from what I was seeing in the federal data. In many cases this would result in a big decline in enrollment, even though all the complete data showed enrollment growth.

I need the data sources to be consistent to avoid these kinds of issues.

I’m writing this on Sunday and hoping to publish on Monday, so writing all the schools with dodgy data and waiting for them to provide their own figures is out of the question. Here’s the kludge I settled on:

Obtain an enrollment growth figure for all the Bellevue private schools that have complete data without school name confusion from the state.

Sum the federal enrollment numbers from 2019.

Estimate the 2021 figure by scaling up the 2019 federal sum accordingly.

This gets us an estimate of 990 additional students enrolled in private schools in Bellevue from 2019 to 2021.

Feel free to check my math in this Excel workbook.

Home School Growth

RCW 28A.200.010(1) requires that parents register with the school district that their home is located in if they plan to homeschool their kids. The state has a page with home school data going back to 2019.

This is a simple calculation. BSD had 161 registered homeschool students in 2019, and 224 in 2021. We picked up 63 registered students.

I don’t know what the compliance rate is for registering as a homeschooler.

Exploring Public School Enrollment Data

Was there a widespread decline in enrollment for all public schools? What metrics are correlated with enrollment changes? Let’s find out!

I’m using enrollment figures from the state’s Data Portal. To limit the number of districts displayed, make data wrangling easier, and compare Bellevue with districts of like size, I limited the charts to districts that started 2019 with more than 10,000 students.

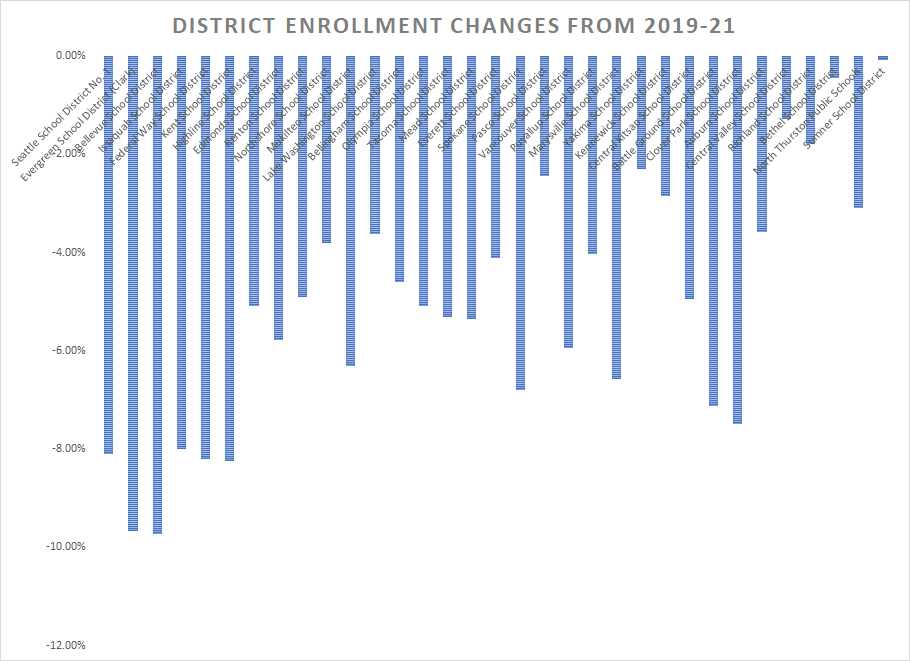

First off, every district in the set lost students since 2019. Bellevue School District and Evergreen School District, in Vancouver, were hit especially hard, losing 9.73% and 9.68%, respectively. Here’s a chart:

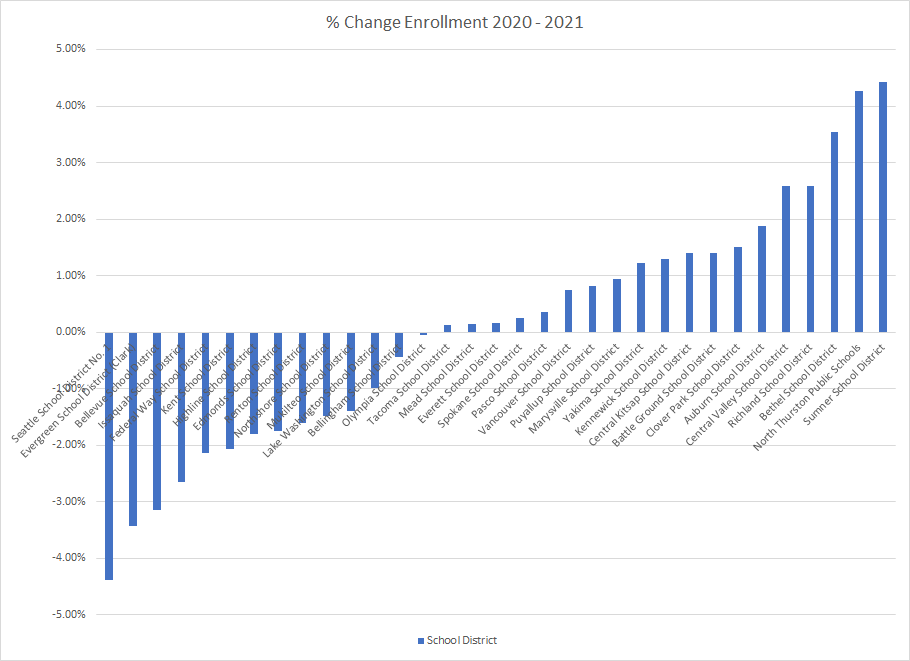

However, this looks very different when looking at enrollment changes from 2020 to 2021:

More than half the districts actually added students. Every district save for one, Seattle, reversed their trend, and either gained students or lost a lower percentage than they had from 2019 to 2020. Bellevue School District lost 6.47% of students from 2019-2020 and lost another 3.15% from 2020 to 2021.

What correlates with this kind of growth or decline? I tried looking at a few things. Note that district boundaries are messy, so in a few instances I chose a geographic proxy for the district. If the district is named after a city, I looked at data for that city. All data are from U.S. Census Quick Facts.

First, and put forward by the district as one of the reasons for the enrollment drop, home prices. I plotted median home price per the U.S. Census vs enrollment changes from 2020-21:

There appears to be some relationship here, but it’s not super explanatory. Below a median value of $500,000 there appears to be almost no relationship. Sumner had the greatest growth at a median home value of $390,700, and Evergreen had the second greatest decline with a median home value of $343,900.

You can see that the R-squared, a measure of how well the trendline fits, is 0.3675. Higher numbers mean better fit.

I had another idea: maybe this tracks with parent education. I plotted percent of the population holding a 4 year degree versus enrollment changes:

That fits about the same as wealth.

I looked at my Quick Facts table for something else to try, and density struck me as a good option. I’ve got a sneaking suspicion that pandemic-related school policies play a big part in the enrollment changes. Anecdotally, the pandemic is taken more seriously in the middle of cities than it is in rural areas. Maybe density would have a greater correlation. Indeed it did:

Look at that R-squared, 0.6176! Twice as tightly correlated with the enrollment changes than home value! Even Seattle, total outlier on density, is pretty close to that regression line.

I set out to look at political views as well, but the data is very messy. I tried to get 2020 election results by city, but that doesn’t exist. I can get it by county, or by precinct, and the precinct data doesn’t follow a predictable pattern for which precinct names map to which cities.

On the budget

The district says they want to be diligent with tax payer money, and that’s part of why they think closing schools is a good idea. Let’s look at what they’re spending our money on. I’m using F-195 budgets posted on the district’s website.

Disclaimer: I’m a total novice, this is my first time looking at these budgets and I could be making bad assumptions. Please let me know if I have made any mistakes.

First, what’s the gap they need to close? Let’s take a look:

The general fund has a deficit of $2.9 million and the transportation fund has a deficit of $2.2 million. The Capital Projects has a big deficit, but I’m going to ignore that: $170 million of the $185 million capital projects fund goes to buildings and sites. We can stop building / renovating / acquiring land.

I’m also going to assume that these are broken out this way because these dollars aren’t fungible. If we’re low on paper for the copiers in the central admin building, we can’t divert some money from the transportation fund or the ASB fund to cover it.

So really, we’re looking just at the $2.9 million deficit in the general fund. The general fund pays for salaries, supplies, building administration, central administration, and many other things.

Conveniently, the F-195 already gives us a view of high-level categories as well as budgets in prior years:

Huh. We sure are growing large parts of the budget even as enrollment declines.

Since 2020 we grew Teaching Support from $58.5 million to $75.2 million, a $16.7 million increase.

Central Administration grew from $25.5 million to $30.2 million, a $4.7 million increase.

We grew Other Supportive Activities from $37.2 million to $52.6 million, a $15.4 million increase.

And we’re closing schools? To cover a $2.9 million deficit? Let’s take a closer look at those two high growth activities, Teaching Support and Other Support:

Guidance counselors and health together have risen by $11.7 million.

In Other Support, the two Operation categories together nearly doubled, going from $6.2 to $11.9 million. Looking further down the budget, I can see that activity code 52 maps to pupil transportation, and code 44 seems to be mostly food services.

Let’s look at Central Administration, where the budget gets made:

What is “Supv Inst”? Supervision of instructors? We grew that by $1.7 million.

I’m thinking “Busns Off” is business office, it grew by $1.1 million.

Public relations grew by more than 50%, going from $789,955 to $1.2 million.

Even the Board of Directors gave itself an extra $483,313 since the start of the pandemic.

There’s enough growth in Central Administration alone to cover the whole $2.9 million deficit.

Closing thoughts

In closing:

It’s far from certain that the child population is shrinking.

It’s likely that factors other than how many kids we have are driving public school enrollment trends.

We could make some pretty small cuts and delay making this decision for a few years to see if this three year trend continues indefinitely. It’s already trending in the right direction!

Why write all of this? Well, I’m angry.

While I did put many hours into research and writing, checking that forecast against the Census data took maybe five minutes. Getting a general sense of whether private school enrollment was going up or down took maybe another ten minutes.

We should be able to depend on our leaders to ask very basic questions before deciding to go whole-hog on closing schools, but apparently we can’t.

I wrote my district’s school board member, Joyce Shui, when this news was announced. I presented the basics of what’s above: the census data disagrees with this projection and the budget has plenty of room. I still haven’t heard back.

My wild guess, informed by parents reaching out on neighborhood groups, is that parents opted out of public schools. I’ve talked with people who say this was because of pandemic policies, and also people that aren’t comfortable exposing their kids to some of the ideological content being presented in schools. At least one person left the state over these concerns.

The path forward from here isn’t to close schools, at least not if we want public schools to thrive and serve everyone. The district needs to regain trust, and closing schools is going to do the opposite of that. If my neighborhood school closes and my wife and I have to send our kids on a bus or drive them anyway, we might just opt for a private school.

I’m unfortunately not optimistic that the district is going to change its plan. No politician seems interested in admitting they made mistakes during the pandemic, and I’ve seen no indication that our school board is exceptional.

Here’s hoping I’m wrong.

Thanks for digging into the data. Please submit this to the public comment feedback at BSD. bsd@bsd405.org. If note that it's a public comment, the board is required to review it and it is recorded.

I agree with all of your points. This is a great comprehensive study and I had the same issues with the demographics data. The demographer is someone from Colorado. He is likely missing "on the ground" feel for the data. Why do we have to get a demographer from Colorado to do this work? It's like asking some guy from China to figure out American politics using infromation gleaned from newspapers.

For correlation between house prices and enrollment, you only looked at the period around covid. I am not surprised that density mattered more than house prices. If you looked at enrollment change over time as a time series vs house prices as a time series, I think you will find that enrollment goes up with house prices. From what I know living here, every parent, of almost every culture backgound/origin buys houses in Bellevue for the schools. It is not economical to live in Bellevue and pay a premium if you don't have kids and can't benefit. I am talking about people who move here not the people who are already here for other reasons previously. If schools dont' matter, places like Burien (Three Three Point) for example become much more attractive. When the demand exceeds the supply, prices go up. So when there is lots of demand for people to move here for the schools, prices and enrollment goes up. The opposite will happen. House prices are a result of enrollment demand, not the driver of it.

Thanks for the detailed writeup!

In a discussion last week, our school principal offered some more detail about the cost of housing and potential impacts - apparently there were ~2100 records transfer requests last year. ~150 were from private schools, but the rest were mostly from schools in comparatively lower cost areas - Snohomish, Eastern Washington, Idaho, and beyond.

I think that could help offer some support to the cost of living rationale, not sure the best way to validate the transfer details independently. If one looks at today's price of homes for sale in the "affordable" neighborhoods of Bellevue it's ~1 - 1.5 million for 1960s construction and ~$3 million+ for new construction.